![]()

Development and Validity of

Philosophies Held by Instructors of Lifelong-learners (PHIL)

![]()

Abstract

The Philosophies Held by Instructors of Lifelong-learners (PHIL) was developed to identify a respondent's preference for one of the major schools of philosophical thought: Idealism, Realism, Pragmatism, Existentialism, or Reconstructionism. The pool of items and the construct validity for PHIL are based on the Philosophy of Adult Education Inventory (PAEI). Item formation and content validity were determined by a series of discriminant analyses. Criterion-related validity was established through a three-part process of comparing PHIL responses to PAEI responses and to the self-report of the accuracy of the group placement on PHIL. Reliability was established through the test-retest process. PHIL is a short, user-friendly instrument that can be completed in 1 to 3 minutes. It is designed for self-assessment for instrumented learning.

Introduction

Many people are involved at various levels in the education of adults. However, the difference between those that are practitioners and those that are professionals is that the professionals know why they do what they do in the teaching-learning transaction. "True professionals know not only what they are to do, but also are aware of the principles and reasons for acting. Experience alone does not make a person a professional adult educator. The person must be also be able to reflect deeply upon the experience he or she has had" (Elias & Merriam, 1980, p. 9). Since "a philosophical orientation underlies most individual and institutional practices in adult education" (Darkenwald & Merriam, 1982, p. 37), this reflective process involves an understanding of educational philosophy and of one's relationship to the various philosophical schools. "Developing a philosophical perspective on education is not a simple or easy task. It is, however, a necessary one if a person wants to become an effective professional educator" (Ozmon & Craver, 1981, p. 268).

An educational philosophy refers to a comprehensive and consistent set of beliefs about the teaching-learning transaction. The purpose of an educational philosophy is to help "educators recognize the need to think clearly about what they are doing and to see what they are doing in the larger context of individual and social development" (Ozmon & Craver, 1981, p. x). Thus, it is simply "to get people thinking about what they are doing" (p. x). By doing this, educators can see the interaction among the various elements in the teaching-learning transaction such as the students, curriculum, administration, and goals (p. 268). This can "provide a valuable base to help us think more clearly" (p. x) about educational issues.

Philosophy is abstract and consists of ideas. "Philosophy is interested in the general principles of any phenomena, object, process, or subject matter" (Elias & Merriam, 1980, p. 3) and "raises questions about what we do and why we do it" (p. 5). It is "more reflective and systematic than common sense" (Darkenwald & Merriam, 1982, p. 38) and "offers an avenue for serious inquiry into ideas and traditions" (Ozmon & Craver, 1981, p. x). Although it is theoretical, it is the belief system that drives an educators actions. Consequently, "your personal philosophy of teaching and learning will serve as the organizing structure for your beliefs, values, and attitudes related to the teaching-learning exchange" (Heimlich & Norland, 1994, pp. 37-38). These abstract concepts are operationalized in the classroom by one's teaching style. "Teaching style refers to the distinct qualities displayed by a teacher that are persistent from situation to situation regardless of the content....Because teaching style is comprehensive and is the overt implementation of the teacher's beliefs about teaching, it is directly linked to the teacher's educational philosophy" (Conti, 2004, pp. 76-77). Recent research confirms this link between the beliefs of educators about educational philosophy and their actions in the classroom (Foster, 2006; Fritz, 2006; O'Brien, 2001; Watkins, 2006).

In order for educators to begin the professional development process of reflecting upon their educational philosophical and relating it to their daily practice, they need to be able to identify their philosophy. In the field of Adult Education, the major instrument that has been developed for this process is the Philosophy of Adult Education Inventory (PAEI) by Lorraine Zinn (2004). The PAEI was based on the descriptions of the schools of philosophical thought in Philosophical Foundations of Adult Education by Elias and Merriam (1980). This important book related the various educational philosophies to the field of adult education and challenged adult educators to think critically about their educational philosophy and how it relates to practice. While the PAEI is a very useful instrument for identifying detailed aspects of one's philosophy, it is time consuming for taking, scoring, and interpreting. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to develop a user-friendly instrument that could be completed rapidly for identifying one's preference for an educational philosophy. This was accomplished by creating and establishing the validity and reliability for an instrument based upon the items in the PAEI.

Development of PHIL

Educational philosophy is "the application of philosophical ideas to educational problems" (Ozmon & Craver, 1981, p. x). Many philosophers wrote about education because "education is such an integral part of life that it is difficult to think about not having it" (p. x). Thus, an analysis of one's educational philosophy can be framed in the context of the major philosophies. In Western thought, these major philosophies are Idealism, Realism, Pragmatism, Existentialism, and Reconstructionism (Ozmon & Craver, 1981). In relating these to the field of adult education, Elias and Merriam (1980) titled these thought systems as Liberal Adult Education, Behaviorist Adult Education, Progressive Adult Education, Humanistic Adult Education, and Radical Adult Education. Unfortunately, the terms "liberal" and "radical" can have political overtones, and therefore one may want to substitute "classical" and "reconstructionist" for these terms (Zinn, 2004, p. 53). While Behaviorism is most often classified as a psychological theory, it has been expanded to include many of the elements of a philosophy and is related to modern Realism (Ozmon & Craver, 1981, pp. 188-190).

Regardless of the terms used, Idealism or Liberal Adult Education believes that "ideas are the only true reality" (Ozmon & Craver, 1981, p. 2) and that the emphasis should be "upon liberal learning, organized knowledge, and the development of the intellectual powers of the mind" (Elias & Merriam, 1980, p. 9). Realism or Behaviorist Adult Education hold "that reality, knowledge, and value exist independent of the human mind" (Ozmon & Craver, 1981, p. 40) with modern Behaviorism emphasizing "such concepts as control, behavioral modification and learning through reinforcement and management by objectives" (Elias & Merriam, 1980, p. 10). Pragmatism or Progressive Adult Education "encourages us to seek out the processes and do the things that work best to help us achieve desirable ends" (Ozmon & Craver, 1981, p. 80) and "emphasizes such concepts as the relationship between education and society, experience-centered education, vocational education and democratic education" (Elias & Merriam, 1980, p. 10). Existentialism or Humanistic Adult Education is concerned with the individual and how humans can create ideas relevant to their own needs and interest (Ozmon & Craver, 1981, p. 167), and key concepts for "this approach are freedom and autonomy, trust, active cooperation and participation and self-directed learning" (Elias & Merriam, 1980, p. 10). Reconstructionism or Radical Adult Education holds that society is in need of constant change and that education is "the most effective and efficient instrument for making such changes in an intelligent, democratic, and humane way" (Ozmon & Craver, 1981, p. 120); consequently, education can be "a force for achieving radical social change" (Elias & Merriam, 1980, p. 11).

The Philosophies Held by Instructors of Lifelong-learners (PHIL) is an instrument that was designed to identify a respondent's preference for one of these major schools of philosophical thought. These philosophical schools differ in (a) their view of what constitutes knowledge, (b) the nature of the learner, (c) the purpose of the curriculum, and (d) the role of the teacher (Darkenwald & Merriam, 1982). While variance may exist among individuals within a philosophical school based on their degree of commitment to these different concepts and to the combination of these different degrees of commitment, the differences among those within a philosophical school are not as great as the differences between the philosophical schools. PHIL only identifies placement in one of these major philosophical schools; it does not identify or measure degrees of variance within these schools. As such, placement is not designed as a label for stereotyping a person; instead, it is designed to stimulate critical thinking and reflection about the teaching-learning transaction (Conti & Kolody, 2004, p. 187).

PHIL was created by an approach that combines various multivariate techniques to construct user-friendly instruments that can be completed quickly and are designed for instrumented-learning situations (Conti, 2002). This process involves using a pool of items from established instruments and then using powerful multivariant statistical procedures to reduce the number of items in the new instrument and to gain clarity for writing the items for the new instrument. This process produces an instrument that quickly and accurately places the respondent in a category. Once this information is known, it can be used for self-analysis and self-improvement.

The first step in the development of any instrument is to identify a pool of potential items for the new instrument. Using the multivariate design, the pool of items for developing PHIL was the 75 items of the Philosophy of Adult Education Inventory (Zinn, 2004). As a result, the construct validity of PHIL is embedded in the validity of the PAEI. The exact wording of the items in PHIL and the instrument's content validity was established by using the results of a series of discriminant analyses with a data base of 371 practitioners. Criterion-related validity was established by comparing the classification on the PAEI for 46 participants to their placement on PHIL, by comparing responses to selected PAEI items for the various groupings on PHIL for 71 teachers, and by self-reported accuracy for these 117 participants. Reliability was established by the test-retest method with 39 practitioners.

Construct Validity

Validity is concerned with what a test actually measures; while there are several types of validity, it has long been established that the three most important types recognized in educational research are construct, content, and criterion-related validity (Kerlinger, 1973, p. 457). These may be established in a variety of ways; however, they should be compatible with the overall purpose of the test (Borg & Gall, 1983, p. 275).

Construct validity assesses the underlying theory of the test, and it asks the fundamental question of what the instrument is really measuring (Gay & Airasian, 2000, p. 167). It is the extent to which the test can be shown to measure hypothetical constructs which explain some aspect of human behavior (Borg & Gall, 1983, p. 280). It is the element that allows for the assigning of "meaning" to the test (Kerlinger, 1973, p. 461). The process of establishing construct validity for PHIL was to use the items from the PAEI (Zinn, 2004) as a pool of items for developing the new instrument. Thus, the construct validity for PHIL was derived from the established validity for the items of the PAEI.

The database for constructing PHIL consisted of 371 responses from community college instructors (Hughes, 1995), vocational rehabilitation professors (O'Brien, 2001), and adult education practitioners in Oklahoma and Montana. Other instruments formed using the multivariate design have started with cluster analysis. With this statistical procedure,

Clusters are formed by grouping cases into bigger and bigger clusters until all cases are members of a single cluster....At every step, either individual cases are added to clusters or already existing clusters are combined. Once a cluster is formed, it cannot be split; it can only be combined with other clusters. Thus, hierarchical clustering methods do not allow cases to separate from clusters to which they have been allocated. (Norusis, 1988, p. B-73)

However, since PHIL is concerned with placing respondents into existing and well-established philosophical groups rather than with uncovering inherent groups that may exist among the participants, cluster analysis was not used in the formation of PHIL. Instead, the logic of cluster analysis was applied to the database. That is, it was assumed that groups existed in the data in a hierarchical order. Just as the logic of experimental design can be used to understand other designs (Yin, 1994, p. 9), the logic of cluster analysis suggests that two distinct groups exist at the two-cluster stage. Based upon descriptions of the five philosophies in the PAEI, it was hypothesized that the basic difference that separated the various philosophies at the two-cluster level was whether the philosophy supported either a learner-centered approach or a teacher-centered approach to learning. Idealism and Realism were grouped as teacher-centered because these philosophies place a strong emphasis on the actions of the teacher to impart knowledge deemed necessary for the student to know. Pragmatism, Existentialism, and Reconstructionism were grouped as learner-centered because of their emphasis on the process of the personal development of the learner. These groupings were used for conducting discriminant analyses to get the wording for the items of PHIL and to establish content validity. The logic for making the decision to group the respondents based on the concept of being either teacher-centered or learner-centered was supported by the extremely high accuracy rate in correct classification in these discriminant analyses.

Thus, the construct validity for The PHIL was established by using the items from the valid and reliable PAEI (Zinn, 2004). The major difference between the five philosophical schools identified by this instrument was assumed to be their support of either a teacher-centered or a learner-centered approach to education. Groupings based on this concept were used for discriminant analyses which not only provided content validity data but also confirmed the accuracy of this logical grouping of the philosophical schools.

Content Validity

Content validity refers to the sampling adequacy of the content of the instrument (Gay & Airasian, 2000, p. 163). Although content validity is usually based on the expert judgement, the content validity for PHIL was assessed statistically because for PHIL content validity is concerned with the degree to which the items are representative of the five philosophical schools upon which the pool of items from the PAEI is based. Therefore, a series of discriminant analyses were conducted to determine the differences between each grouping. Discriminant analysis is a powerful multivariate statistical procedure for examining the differences between groups using several discriminating variables simultaneously (Kachigan, 1991, p. 216; Klecka, 1980, p. 5). This procedure produces a structure matrix which shows the interactions within the analysis and which can be used for naming the process that separates the groups (Klecka, 1980, pp. 31-34). When discriminant analysis is used with groups formed by cluster analysis or with groups like those in PHIL, it can be used for identifying the process that separates the groups and for describing the groups (Conti, 1996, p. 71). Several discriminant analyses were conducted. After each one, the findings from the structure matrix for the discriminant analysis were used to determine the wording of the items.

For the first analysis, the 371 participants were grouped as Teacher-Centered or Learner-Centered. The Teacher-Centered group consisted of the 115 participants in the philosophical schools of Idealism and Realism. The Learner-Centered group contained the 256 participants in the philosophical schools of Pragmatism, Existentialism, and Reconstructionism. The relevant items in the structure matrix of the discriminant analysis for these two groups were 1d, 2d, 5a, 5e, 6e, 7a, 8c, 9b, 13e, and 14e. Collectively, they indicated that the process that separated the two groups was the amount of teacher control in the learning environment. While the Teacher-Centered group supported control that fostered systematic movement toward defined objectives, the Learner-Centered groups favored a flexible environment that promoted learner's interests. This process was 87.6% accurate in discriminating between the two groups. The precise item that describes this process made up the first item in PHIL.

The second item in PHIL separates the Pragmatists and Reconstructionist from the Existentialists. For this analysis, the size of the groups were as follows: Pragmatists--191, Existentialists--56, and Reconstructionists--9. The relevant items in the structure matrix were 5a, 5e, 6a, 6b, and 8d . The process that separated the groups was the focus of educational material. While the Existentialists group focused on the individual, both the Pragmatist and Reconstructionist groups focused on a problem external to the learner that can be addressed through instruction. The process that separated the Existentialists from the group of Pragmatists and Reconstructionists was 87.1% accurate.

The third item in PHIL separates the Pragmatists and Reconstructionists. For this analysis, the Pragmatist group contained 56 respondents, and the Reconstructionist group contained 9 respondents. The relevant items in the structure matrix were 1a, 7e, 9d, 14d, and 15d. The process that separated the groups was the purpose of the educational process. While the Pragmatist group focused on the learner's feelings, the Reconstructionist groups stressed the social and political impact of the learning. The process that separated the Pragmatists from the Reconstructionists was 95.0% accurate.

The fourth item in PHIL distinguishes the Idealists from the Realists. For this analysis, the Idealist group contained 30 respondents, and the Realist group contained 85 respondents. The relevant items in the structure matrix were 9b, 10b, and 13b. The process that separated these two groups focused on feedback to the learner. While both groups favored providing feedback to the learner, the Realists supported it more strongly. This process was 97.4% accurate in separating the groups.

Thus, content validity was established by using a series of discriminant analyses to determine the exact process that separates the various philosophical schools. The structure matrix from each analysis was used to form the item for each item in the instrument. While PHIL has only a few items, each item is based on the powerful multivariate procedure of discriminant analysis, and each question identifies the process that separates two groups of philosophical ideas. Instead of using an approach which involves summing multiple attempts to identify a characteristic, PHIL uses discriminant analysis to precisely describe the content for each item.

Criterion-Related Validity

Criterion-related validity compares an instruments scores with an external relevant criterion variable (Huck, 2004, p. 90). While establishing criterion-related validity for most instruments is usually the very straight-forward procedure of comparing the new instrument to an established instrument or behavior, it is a more difficult procedure with an instrument created in the model used for PHIL. This is because this approach uses a multivariate process to create a new instrument from items that are scored in a univariate format. Thus, the process of establishing criterion-related validity in essence involves trying to compare a whole that results from a synergistic analysis to its parts. This is difficult because as the cliche suggests, the total is greater that sum of its parts. Therefore, three separate things were done to assess the criterion-related validity of PHIL. First, criterion-related validity was established by comparing the group placement on PHIL to the preferred group rating on the PAEI; this provided a measure of the comparison of PHIL with the instrument from which the items were drawn to form it. Second, responses were collected for the various PAEI items from the structure matrices that were used to construct the items in PHIL. The means were compared for each of the groups involved in forming the item; this provided a comparison between the responses of the philosophical groups and the specific items from the PAEI that were used to identify them. Finally, the participants were asked to self-report on the accuracy of the PHIL placement for them after they had read a description of the philosophical groups; this provided a check between the response on PHIL and the real-world of the respondent.

Both the PAEI and the PHIL were completed by 46 educators who had taken a course on the foundations of adult education. Participants responded to both instruments on the Internet. Responses on the PAEI were summed, and the scores for each philosophical school were standardized as a percentage of the respondent's total score for all items of the instrument (O'Brien, 2001). The philosophical school with the highest percentage score was used as the person's philosophical preference. The correlation between the highest score on the PAEI and the placement on PHIL was .785 (p < .001). The group was distributed among the various philosophical schools as follows: Idealist--4 (8.7%), Realists--8 (17.4%), Pragmatists--7 (15.2%), Existentialists--23 (50%), and Reconstructionists--4 (8.7%). Almost all (91.3%) of the respondents felt that PHIL had placed them in the proper philosophical school.

In a typical criterion-related validity analysis, scores on one instrument are compared to those on another. However, different sets of items on PHIL are used to identify the various philosophical groups. Therefore, separate analyses were conducted for each set of items that were used to distinguish the various groups. Responses were gathered from 71 teachers in the Tulsa Public Schools for PHIL and for the items from the PAEI that were in the structure matrices for forming the items in PHIL. Thus, the group placement in PHIL was compared to the criterion of the items from the PAEI that were used from group placement. Ten items were used from the structure matrix for the discriminant analysis between the teacher-centered and learner-centered approaches to form the first item in PHIL. The 48 in the learner-centered group scored higher as was expected on eight of these items than the 23 in the teacher-centered group; they scored slightly lower on one item; the groups were equal on the other item. There were three items that separated the Idealists from the Realists. There was only one Idealist in the group, and on all three of the items, the Idealist scored lower as was expected than the 22 Realists. Five items separated the Existentialists from the Pragmatists and the Reconstructionists. The 37 Existentialists scored lower as was expected than the Pragmatists and Reconstructionists on 3 of the 5 items. However, on two of the items they scored higher. Finally, five items were used to separate the Pragmatists from the Reconstructionists. The six Reconstructionists scored higher as was expected than the five Pragmatists on all five of the items. Thus, for each set of items from the various structure matrices, the groups identified by PHIL scored as was expected on the items that were used to form the items for PHIL; these scores were strong for three of the four analyses while they were mediocre for one. Moreover, 93% of the respondents felt that PHIL had placed them in the correct philosophical group.

Thus, because of the multivariate procedure that was used for creating PHIL, criterion-related validity was assessed in three different ways. Because of the strength of the correlation between placement on PHIL and on the PAEI, because of the same relationship between scores on the selected items in the PAEI and placement on PHIL, and because of the extremely high testimony by respondents of the accuracy of the group placement by PHIL, it was judged that PHIL has criterion-related validity.

Reliability

"Reliability is the degree to which a test consistently measures whatever it is measuring" (Gay & Airasian, 2000, p. 169). Reliable may be measured as either stability over time or as internal consistency. The reliability of the PHIL was established by the test-retest method which addresses "the degree to which scores on the same test are consistent over time" (p. 171). PHIL was administered to a group of 39 adult education practitioners with a 2-week interval. The coefficient of stability for these two testing was .742 (p < .001).

Description of PHIL

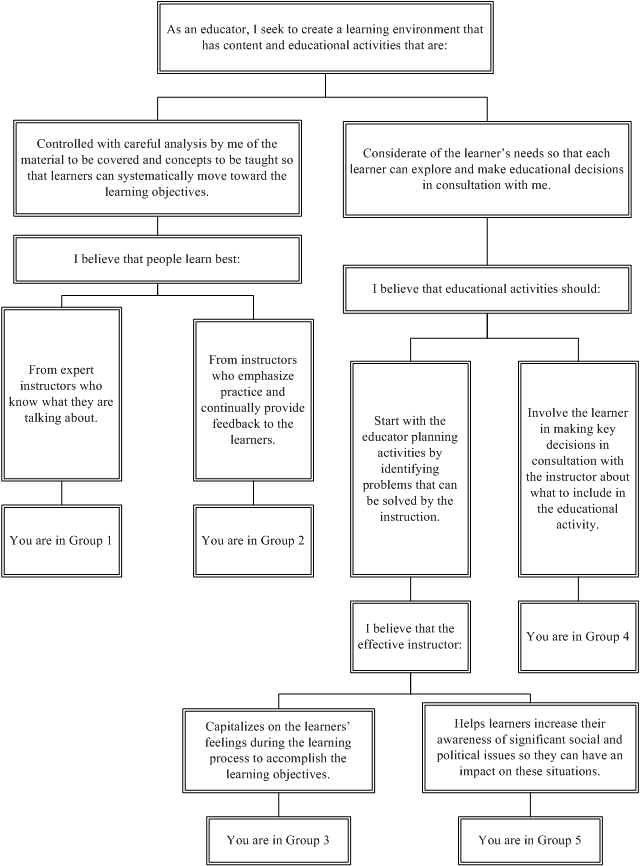

PHIL consists of four items that are organized in a flow-chart design (see Figure 1). Each item begins with a sentence stem that leads to two options. Each option leads the respondent to another box which either instructs the respondent to proceed to another page with an additional item on it or which provides information about the respondent's correct group placement. Once the group placement is identified, the respondent is directed to the page with the descriptions of the various educational philosophies. By responding to two or three items, a respondent's preference for an educational philosophy can be identified. Depending upon a person's reading level, PHIL can be completed in approximately 1 to 3 minutes. Although PHIL appears to be a very simple instrument, its contents are based on powerful multivariate statistical procedures.

Figure 1: Flow Chart for Items in PHIL

The items for PHIL can be organized in a variety of formats for administering the instrument. First, it can be in a bound booklet with each item on a separate page and with each option for an item having a box which directs the respondent to the next appropriate action. The descriptions of the philosophies either can be attached as the final page of the booklet or can be on a separate sheet. Second, it can be printed in a landscape format on a single sheet of paper which is folded one-fourth of the way in from each side to form flaps that can be opened. In this format, the directions and first item stem are printed on the front of one flap and one of the two options for completing the stem are printed on the front of each of the flaps. The next appropriate item in the flow chart is printed on the back of each flap. The last item can be printed on the back of the folded sheet, and the descriptions of the philosophies can be printed on the front center of the sheet and revealed when the flaps are opened. Third, the items can be simply printed on colored cards with directions after each option sending the respondent to the next appropriate card. Finally, the items can be entered electronically in a computer with the items linked to follow the flowchart (see http://www.conti-creations.com/PHIL.htm). Whichever form is used, the directions should be an appropriate variation of the following: "Read the sentence stem for the first item. Select the response that best fits you, and follow the link to the next item that you should use. Only read the items to which you are sent. Continue this process until you are instructed to the Description of PHIL sheet."

Discussion

"Most adult educators want to be the best they can be and are willing to work to improve. They can do so by understanding how their beliefs and behaviors relate to teaching and learning" (Heimlich & Norland, 1994, p. 3). This path to continuous self-improvement and professional development should start with an assessment of one's educational philosophy. Respected leaders in the field of adult education have long stressed the need for systematically identifying one's working philosophy and using it to guide practice (Apps, 1976, 1989). Developing such a conscious knowledge of one's beliefs and values can foster a "sensitivity to what we do and why we do it", help "us consider alternatives--other ways of doing what we do", and nurture an awareness of "our fundamental beliefs and values" (Apps, 1989, pp. 17-18); "ultimately, an analysis of our foundations as a teacher can help empower us" (p. 18). In addition, "many current debates on educational policy and practice could be conducted more rationally if basic philosophical differences were clarified" (Darkenwald & Merriam, 1982, p. 38). PHIL can be used as a tool to initiate this critical analysis.

Using PHIL in this way is a form of instrumented learning. Instrumented learning uses instruments to provide information for participants so that it can be used for various types of self-improvement (Blake & Mouton, 1972). This information is provided in a context and in relationship to a particular model so that the participant can use it to focus learning. With PHIL, the goal is to get a quick and accurate group placement so that the planning of learning can begin.

A key element of instrumented learning is metacognition. "Metacognition is popularly conceived of as thinking about the process of thinking" (Fellenz & Conti, 1989, p. 9). "Simply put, learning instruments provide adult learners with metacognitive references for reflecting upon their experiences. Thus, the instrumented learning process is analogous to the learning process of reflective practice" (Hulderman, 2003, p. 86). Since one's educational philosophy encompasses the person's values and beliefs, an awareness of these choices can inform the educator of things that need to be done to implement adult learning principles. While these learning principles are stable, their are various ways to implement them. Knowing and reflecting upon one's personal philosophy can help educators determine how to more effectively apply these learning principles; this in turn can lead to more reflection. Along the way, "your working philosophy may change--indeed, in most instances it will change--as you face new challenges and problems. But the process for examining and find-tuning your beliefs can serve as a constant" (Apps, 1989, p. 27). For this journey to professionalism, tools such as PHIL are a must.

![]()

References

Apps, J. W. (1976). A foundation for action. In C. Klevins (Ed.), Materials and methods in continuing education (pp. 18-26). Los Angles, Klevens.

Apps, J. W. (1989). Foundations for effective teaching. In E. Hayes (Ed.), Effective teaching styles (pp. 17-28). New Directions of Continuing Education, 45(Fall). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Blake, R. R., & Mouton, J. S. (1972). What is instrumented learning? Part I--Learning instruments. Industrial Training International, 7(4), 113-116.

Borg, W., & Gall, M. (1983). Educational research (4th ed.). New York: Longman.

Conti, G. J. (1996). Using cluster analysis in adult education. Proceedings of the 37th Annual Adult Education Research Conference (pp. 67-72). University of South Florida, Tampa.

Conti, G. J. (2002). Constructing user-friendly instruments: The power of multivariant statistics. Proceedings of the 21st Midwest Research-to-Practice Conference in Adult, Continuing, and Community Education (pp. 43-48). DeKalb, IL: Northern Illinois University.

Conti, G. J., & Kolody, R. C. (2004). Guidelines for selecting methods. In M. W. Galbraith (Ed.), Adult learning methods: A guide for effective instruction (3rd Ed.). Malabar, FL: Krieger Publishing Co.

Darkenwald, G. G., & Merriam, S. B. (1982). Adult education: Foundations of practice. New York: Harper & Row.

Elias, J. L., & Merriam, S. (1980). Philosophical foundations of adult education. Huntington, NY: Robert E. Krieger Publishing Co.

Fellenz, R. A., & Conti, G. J. (Eds.). (1989). Learning and reality: Reflections on trends in adult learning (Information Series No. 336). Columbus, OH: ERIC Clearinghouse on Adult, Career, and Vocational Education.

Foster, V. L. (2006). Teaching-learning style preferences of special education teacher candidates at Northeastern State University in Oklahoma. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Oklahoma State University, Stillwater.

Fritz, A. (2006). Educational philosophies and teaching styles of Oklahoma elementary public school ESL teachers. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Oklahoma State University, Stillwater.

Gay, L. R., & Airasian, P. (2000). Educational research: Competencies for analysis and application (6th Ed.). Columbus, OH: Merrill Publishing Co.

Huck, S. W. (2004). Reading statistics and research (4th Ed.). Boston: Pearson.

Hughes, C. L. (1997). Adult education philosophies and teaching styles of faculty at Ricks College. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Montana State University.

Hulderman, M. A. (2003). Decision-making styles and learning strategies of police officers: Implications for community policing. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Oklahoma State University, Stillwater.

Kachigan, S. K. (1991). Multivariate statistical analysis: A conceptual introduction (2nd Ed.). New York: Radius Press.

Kerlinger, F. N. (1973). Foundations of behavioral research. New York: Holt, Reinhart, & Winston.

Klecka, W. R. (1980). Discriminant analysis. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage Publications.

Norusis, M. J. (1988). SPSS/PC+ advanced statistics V2.0: For the IBMPC/XT/AT and PS/2. Chicago: SPSS.

O'Brien, M. D. (2001). The educational philosophy and teaching style of rehabilitation educators. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Oklahoma State University, Stillwater.

Ozmon, H. A., & Craver, S. M. (1981). Philosophical foundations of education (2nd Ed.). Columbus, OH: Merrill Publishing Co.

Watkins. J. B. (2006). The educational beliefs and attitudes of Title 1 teachers in Tulsa Public Schools. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Oklahoma State University, Stillwater.

Yin, R. K. (1994). Case study research: Design and methods (2nd Ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Zinn, L. M. (2004). Exploring your philosophical orientation. In M. W. Galbraith (Ed.), Adult learning methods: A guide for effective instruction (3rd ed.). Malabar, FL: Krieger Publishing Co.

![]()

Appendix

The following are the descriptions of the five groups that are used in PHIL. These are based on descriptions of the philosophies in Philosophical Foundations of Education by Ozmon and Craver (1981).

Group 1 is Idealism which holds that ideas are the only true reality. This philosophy goes back to ancient Greece and claims greats such as Socrates and Plato. This school seeks to discover true knowledge rather than create it. The aims of the philosophy are to search for truth and further the character development of learners. The role of the teacher is to serve as a guide for immature learners, judge important material, and model appropriate behavior. The instructional process is holistic, seeks to develop critical thinkers, and deals with broad concepts rather than specific skills. This is a content-centered approach to education with a heavy emphasis on seeking universal truths and values and with a strong and defined role for the teacher.

Group 2 is Realism which holds that reality exists independent of the human mind; matter in the universe is real and independent of man's ideas. This philosophy grew out of the Age of Enlightenment and strongly supports the use of the scientific method. Its aims are to understand the world through inquiry, verify ideas in the world of experience, teach things that are essential and practical, and develop the learner's rational powers. The instructional process seeks to teach fundamentals, encourage specialization, and teach the scientific method. The role of teacher is to present material systematically, encourage the use of objective criteria, and be effective and accountable. Behaviorism is congruent with this broader teacher-centered philosophy.

Group 3 is Pragmatism or Progressivism and is associated strongly with the works of John Dewey. It seeks to inquire and to then do what works best; that is, it seeks to be pragmatic. However, everything centers on the human experience. It seeks to promote democracy by developing strong individuals to serve in a good society. It supports diversity because education is the necessity of life. Its aims are to seek understanding, coordinate all environments into a whole, teach a process of inquiry, and promote personal growth and democracy. The instructional process is flexible with a concern for individual differences and for problem solving and discovery. In this learner-centered approach, the role of the teacher is to identify the needs of the learner and to serve as a resource person.

Group 4 is Existentialism or Humanism and draws heavily from the ideas of Carl Rogers. This philosophy focuses on the individual and believes that individuals are always in transition. People interpret the world from their own perceptions and construct their own realities. Its aims are to promote self-understanding, involvement in life, an awareness of alternatives, and the development of a commitment to choices. Learning is viewed as a process of personal development which seeks to provide learners with options. The role of the instructor in this learner-centered philosophy is to be a facilitator. The cornerstone of this philosophy is trust between the teacher and learner.

Group 5 is Reconstructionism. It strongly believes that education can be used in reconstructing society. In order to achieve social justice and true democracy, change rather than adjustment is needed. This philosophy is futuristic and takes a holistic view of problems. Its aims are to encourage social activism and the development of change agents. Its purpose is to empower people to think critically about their world, develop decision-making abilities, get involved in social issues, and take action. The role of the teacher in this learner-centered philosophy is to help learners develop problem-posing skills and lifelong-learning skills. This school of thought has been greatly influenced by the work of Paulo Freire and Myles Horton.

![]()